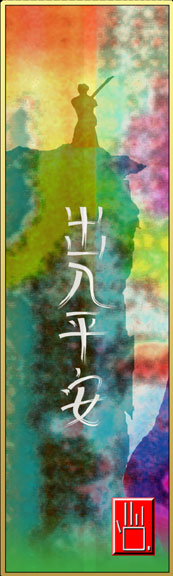

On The Way: The Daily Zen Journal

Mystery of Immovable Mind

Takuan (1573-1645)

Takuan’s Letter to Yagyu Munenori

The second question is: Where is the mind to be after all?

I answer: “The thing is not to try to localize the mind anywhere but to let it fill up the whole body, let it flow throughout the totality of your being. When this happens you use the hands when they are needed, you use the legs or the eyes when they are needed, and no time or no extra energy will be wasted. The localization of the mind means it’s freezing. When it ceases to flow freely as it is needed, it is no more the mind in its suchness.”

The Mind of No-Mind

A mind unconscious of itself is a mind that is not at all disturbed by affects of any kind. It is the original mind and not the delusive one that is chock-full of affects. It is always flowing, it never halts, nor does it turn into a solid.

As it has no discrimination to make, no preference to follow, it fills the whole body, pervading every part of the body, and nowhere standing still. It is never like a stone or a piece of wood. If it should find a resting place anywhere, it is not a mind of no-mind. A no-mind keeps nothing in it. It is also called munen, “no-thought.”

When munen or mushin is attained, the mind moves from one object to another, flowing like a stream of water, filling every possible corner. For this reason the mind fulfills every function required of it. But when the flowing is stopped at one point, all the other points will get nothing of it, and the result will be a general stiffness and stoppage. The wheel revolves when it is not too tightly attached to the axle. When it is too tight, it will never move on.

If the mind has something in it, it stops functioning, it cannot hear, it cannot see, even when a sound enters the ears or a light flashes before the eyes. To have something in mind means that it is preoccupied and has no time for anything else. But to attempt to remove the thought already in it is to refill it with another something. The task is endless. It is best, therefore, not to harbor anything in the mind from the start.

Takuan (1573-1645)

To supplement Takuan, the following story is given to illustrate the doctrine of “no-mind-ness”:

A woodcutter was busily engaged in cutting down trees in the remote mountains. An animal called “satori” appeared. It was a very strange-looking creature, not usually found in the villages. The woodcutter wanted to catch it alive.

The animal read his mind: “You want to catch me alive, do you not?” Completely taken aback, the woodcutter did not know what to say, whereupon the animal remarked, “You are evidently astonished at my telepathic faculty.”

Even more surprised, the woodcutter then conceived the idea of striking it with one blow of his ax, when the satori exclaimed, “Now you want to kill me.” The woodcutter felt entirely disconcerted, and fully realizing his inability to do anything with this mysterious animal, he thought of resuming his business. The satori was not charitably disposed for he pursued him, saying, “So at last you have abandoned me.”

The woodcutter did not know what to do with this animal or with himself. Altogether resigned, he took up his ax and, paying no attention whatever to the presence of the animal, vigorously and singlemindedly resumed cutting trees. While so engaged, the head of the ax flew off its handle, and struck the animal dead. The satori, with all its mind-reading sagacity, had failed to read the mind of “no-mind-ness.”

In the song it says:

It is the very mind itself

That leads the mind astray;

Of the mind,

Do not be mindless.

Takuan Soho was Zen monk, calligrapher, painter, poet, and tea master. In his writings we find the unity of Zen and the sword expressed as advice to one of the leading swordmasters of the day, Yagyu Munenori.

Zen speaks of the sword of life and the sword of death, and it is the work of a great Zen master to know when and how to wield either one of them. Manjusri carries a sword in his right hand and a sutra in his left. The sacred sword of Manjusri is not to kill any sentient beings, but our own greed, anger, and folly. It is directed toward ourselves, for when this is done the outside world, which is the reflection of what is within us, becomes also free of anger, greed, and folly.

Taken from Zen and Japanese Culture D.T. Suzuki 1959

The Way of the Sword is a Zen Way of action emerging from stillness and difficult to understand without practice. This kind of action expresses the depth of our spiritual nature and calls for immediate response before intellect arises to interfere. Few today travel the path of the warrior-sage as the Way has become obscured.

The kensei learns to act totally, beyond ambivalence,with the vitality of his entire being. Total action is the manifestation of Being-Becoming itself. When the time for action is over, the kensei returns naturally to stillness.

Light of the Kensei- G. BlueStone

Returning to Stillness,

Elana, Scribe for Daily Zen